True polar wandering: a change 84 million years ago

[ad_1]

True polar wandering: a major change

The Tokyo Institute of Technology said on October 18, 2021 that one of its researchers had helped uncover new evidence for so-called true polar wandering. It is the still controversial idea that the solid outer shell of the Earth may have shifted relative to the Earth’s axis of rotation some 84 million years ago, at the end of Upper Cretaceous period. A declaration from Tokyo Tech said:

Hold on to your hats, as scientists have found more evidence that the Earth rocks every now and then. We know that continents move slowly due to tectonic plates. But continental drift only pushes the tectonic plates against each other. In recent decades, scientists have wondered whether the solid outer shell of the Earth can oscillate or even tilt relative to the axis of rotation. Such a displacement of the Earth is called true polar wandering. But the evidence for this process has been controversial. New search published in Nature Communication … Provides some of the most compelling evidence to date that such a planetary shift has indeed occurred in Earth’s past.

Geologist Ross mitchell at the Beijing Institute of Geology and Geophysics led the new research. Joe kirschvink from Tokyo Tech and also Caltech was part of the research team.

A controversial idea

Kirschvink, in particular, has long specialized in the measurement of residual magnetic fields in rock. These measurements can reveal the latitude at which the rock formed millions or billions of years ago. According to a 2016 article in Science:

The technique led [Kirschvink] to powerful and influential ideas.

[For example], in 1992, he gathered evidence that glaciers nearly covered the globe over 650 million years ago, and suggested that their subsequent withdrawal from Snowball Earth (a term he coined) triggered a evolving lottery which would become the Cambrian explosion 540 million years ago. And he was important among a group of scientists who in the 1990s and 2000s argued that the magnetic crystals of a famous Martian meteorite, Allan Hills 84001, were fossilized signs of life on the red planet …

“He is not afraid to take risks”, says Kenneth lohmann, a neurobiologist who studies magnetoreception in lobsters and sea turtles at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. “He was right about some things and not others.”

True polar wandering is not this

- This is not a geomagnetic reversal, or a reversal of the Earth’s magnetic field, known to have occurred before in Earth’s history.

- This is not plate tectonics, which describes the large-scale movements of large terrestrial plates on Earth and believed to be driven by the circulation of the Earth’s mantle.

- It is not a precession of the Earth, by which the axis of rotation of our world moves slowly, drawing a circle among the stars, causing changes in the identity of our pole star over time.

True polar wandering is this

True polar wandering suggests that if an object of sufficient weight on Earth – for example, an oversized volcano or other heavy land mass – formed far from the Earth’s equator, the force of Earth’s rotation would gradually move the object away from it. the axis around which the Earth rotates. . An oversized volcano far from the Earth’s equator would create a imbalance, in other words. Tokyo Tech’s statement explains:

Earth is a layered ball. It has a solid metal inner core, a liquid metal outer core, and a solid mantle and dominant crust on the surface, which we live on. It all turns like a top, once a day. Because the Earth’s outer core is liquid, the solid mantle and crust are able to glide over it. Relatively dense structures, such as subduction of oceanic plates and massive volcanoes like Hawaii, prefer to be near the equator. Likewise, your arms like to be by your side when you turn on an office chair.

Joe Kirschvink was the first to propose true polar slippage in 1997. And scientists are measuring a small amount of true polar slippage occurring today, very precisely, with satellites. But, over the past few decades, geologists have fiercely debated whether large rotations of the Earth’s mantle and crust have occurred in Earth’s past. And a particular point of contention is whether such a big change happened 84 million years ago, at the end of the Cretaceous. There have been public arguments about this in the newspaper Science, and during numerous scientific meetings, these scientists said.

Fossil magnetism tells the story

Tokyo Tech’s statement explains:

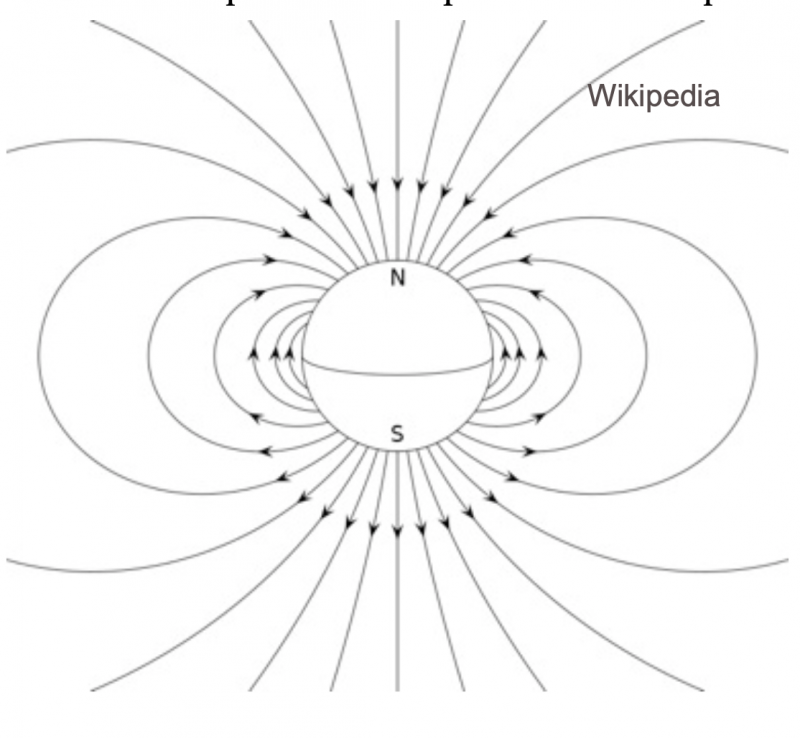

Despite this wandering of the earth’s crust, the earth’s magnetic field is generated by electric currents in the nickel-iron metallic convection liquid of Earth’s outer core. Over long time scales, the overlying wandering of the mantle and crust does not affect the nucleus. This is because these overlying rock layers are transparent to the Earth’s magnetic field.

In contrast, convection models [a roiling motion, like you see in boiling water] in this outer core are in fact forced to dance around the Earth rotation axis. This means that the overall configuration of the Earth’s magnetic field is predictable, spreading out much like iron filings lining up on a small magnetic bar. These data therefore provide excellent information on the direction of the North and South geographic poles. And the tilt gives the distance to the poles (a vertical field means you are at the pole, horizontal tells us it was on the equator).

Many rocks actually record the direction of the local magnetic field as they form, much like a magnetic tape records your music. For example, tiny crystals of the mineral magnetite produced by certain bacteria actually line up like tiny compass needles and become trapped in the sediment as the rock solidifies. This fossil magnetism can be used to track where the axis of rotation moves relative to the crust.

Kirschvink added:

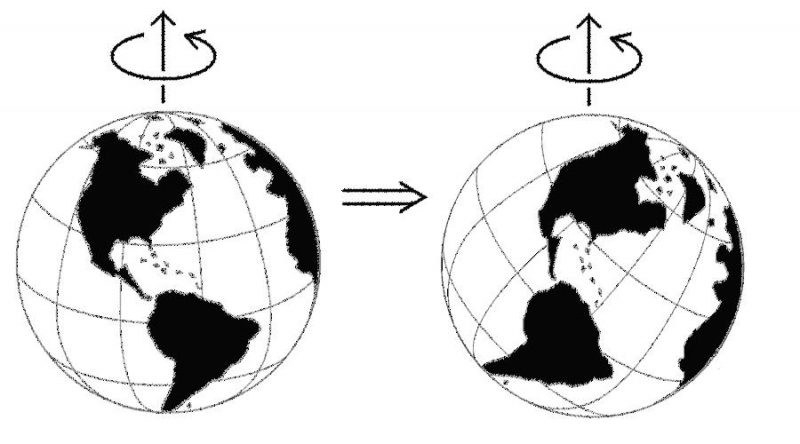

Imagine that you are looking at the Earth from space. A true polar wander would look like the Earth tilting sideways, and what really happens is that the entire rocky shell on the planet – the solid mantle and crust – revolves around the liquid outer core.

Data collection in Italy

As a student, Ross Mitchell – the lead author of the new study – studied the geology of the Apennines in central Italy. He knew the right rocks to sample for fossil magnetism. Tokyo Tech explained:

The international team of researchers then placed their bet. They bet that paleomagnetic data from limestones created in the Cretaceous (between ~ 145.5 and 65.5 million years ago) located in Italy would provide a definitive test. Scientists had already studied the magnetism of younger rocks in the same region almost 50 years ago. These data had indirectly led to the discovery of the asteroid impact that killed the dinosaurs.

Sarah slotznick, co-author and geobiologist at Dartmouth College, explained:

These Italian sedimentary rocks turn out to be special and very reliable because the magnetic minerals are actually fossils of bacteria that have formed chains of the mineral. magnetite.

The team said in their statement:

Test [our] true polar drift assumption, paleomagnetic data with a lot of redundancy is needed. Previous studies, especially some claiming that there is no true polar slippage, have failed to explore enough data points.

The quoted statement Richard Gordon, a geophysicist from Rice University in Houston who was not involved in the study. He commented:

This is one of the reasons it is so refreshing to see this study with its abundant and beautiful paleomagnetic data.

A cosmic yo-yo

Ross, Kirschvink and their colleagues discovered, as predicted by the true polar wandering hypothesis, that Italian data indicates an inclination of about 12 degrees of the planet 84 million years ago. The team also discovered that the Earth appears to have corrected itself after tipping onto its side. It appears that the Earth has reversed its course and turned backwards, for a total excursion of nearly 25 degrees of arc in approximately five million years.

These scientists said:

Certainly it was a cosmic yo-yo.

Image by Ross Mitchell / Tokyo technology.

The researchers used the fossil magnetism of rocks in Italy to acquire a large amount of data. The data provided a record of true polar drift – a major change in the Earth’s outer shell relative to its axis of rotation – 84 million years ago.

[ad_2]